Heat islands in the city

Every tree counts

The warmest winter since weather records began is just coming to an end. The average temperature was 3.4 degrees Celsius above the average for the years 1981 to 2010, the European climate change service Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) reported on 4 March. This gives reason to fear that the coming summer months will also break new temperature records. In the cities, the asphalt will glow, and crossing shadowless places like Zurich's Münsterhof will be a torture.

How do we intend to organize the cooling of our cities in the next 100 years - if climate change starts to hit? Will a bit of city green suffice, distributed according to aesthetic taste? Or can it be a little more specific? Empa – known for its accuracy – has made its first calculations on the Münsterhof in Zurich.

Making climate change more bearable

Aytaç Kubilay works in the Laboratory of Multiscale Studies in Building Physics at Empa and at the Chair of Building Physics at ETH Zurich. He is expert in simulating heat flows in various dimensions – from individual pores in bricks, concrete walls or wood to entire cities. It is quite clear that such a research group is also concerned with climate change and is considering strategies to make the coming warm period more bearable, especially in cities.

The Empa and ETH researcher has chosen Münsterhof in Zurich’s old town for his simulation. A large part of the square is covered with cobblestones, the edge of the Fraumünster church is concreted. There are some cafés and seating facilities, but there are no trees that would provide shade. In addition, the Münsterhof is surrounded by buildings on almost all sides. The facades heat up considerably due to the irradiation of the sun.

Gartentor’s Art Action

In the summer of 2019, the project of the artist Heinrich Gartentor of the Bernese Oberland showed just how much large part of the population are already longing for a green Münsterhof. For four weeks, the square was covered by a rough meadow, which had been specially made for the project by a gardener in Aargau. In addition, there were two shady willows from the Baummuseum Rapperswil. Until the campaign ended on 17 September, the city received many inquiries as to whether the meadow could remain permanently installed on Münsterhof.

Empa researcher Kubilay and his colleagues had nothing to do with Heinrich Gartentor’s art action - even if their results point in the same direction. The researchers chose the site to carry out climate simulations that can also be applied to other places and cities. The calculations show that the temperatures on the Münsterhof would be significantly lower if the square was not paved but covered with earth and grass. Overnight, the ground would cool down more and store less heat during the day. The result would be significantly less heating of the surface.

How will the comfort factor change?

To find out how the assumed change would affect people, Empa researchers use the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). This index indicates how high the temperature actually perceived by passers-by is - it takes into account not only air temperature, but also humidity, surrounding surface temperatures, solar radiation and wind speed.

The UTCI is quite similar to the Celsius temperature scale: values from +38 to +46 mean “very strong heat stress”, from +32 to +38 it means “strong heat stress”, from +26 to +32 it means “medium heat stress”, and in the UTCI range from +9 to +26 people feel most comfortable and feel “no temperature stress”.

The result: even if only a quarter of the paved area at Münsterhof were replaced by a different floor covering, the oven would be deactivated in summer. One possibility would be a pavement made of porous bricks, which could be watered and provide evaporative cooling. A grassy landscape would also help – even if it were not permanently watered and dry out at times. The times of day at which the Münsterplatz UTCI index climbs above 32 (“severe heat stress”), would be significantly shorter with alternative floor covering.

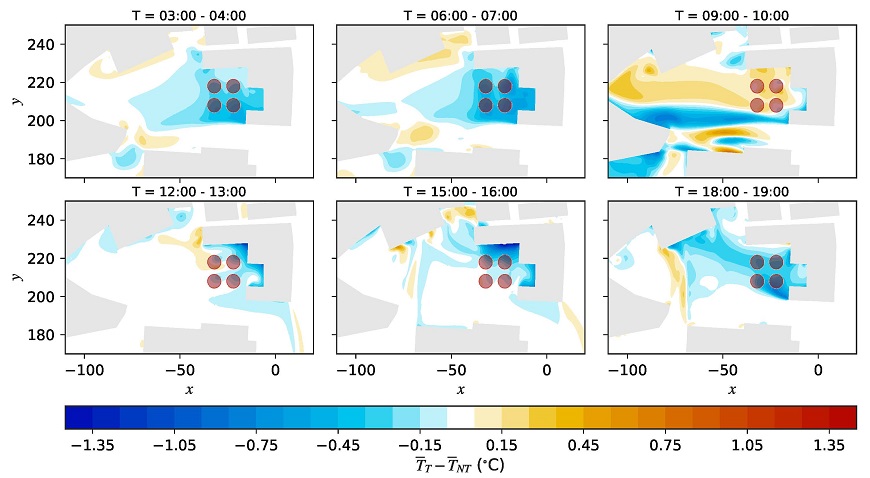

Presence of trees creates a completely different climate

The result would be even clearer if trees were planted on Münsterhof. Aytaç Kubilay and his colleague Lento Manickathan simulated with their software the effect of four narrow standing trees on the northeast side of the square. “The shade of the trees and at the same time their transpiration cooling would greatly reduce the heat stress,” says Kubilay. The perceived temperature would drop by two degrees on large parts of the square. Where the house facades are in the shade, it can even be up to four degrees.

The trees can help cool down the square, but also change the wind-flow field. After the model calculations at Münsterhof, they want to further refine their simulation in order to enable city planners to make detailed predictions on how climate change can be tackled.

Dr. Aytaç Kubilay

ETH Zurich, Chair of Building Physics

Viktor Dorer

Empa, Laboratory for Multiscale Studies in Building Physics

Tel +41 58 765 42 75

In the MDR Wissen program entitled "Krank vor Hitze?", Aytaç Kubilay talks about the greening project at Münsterhof in Zurich.

Broadcast MDR Wissen from November 15, 2020 (in German)

-

Share

Renovation

The path to an energy-efficient building park

Heating, hot water and private electricity consumption consume large amounts of energy and cause high CO2 emissions. Energy-efficient renovations of buildings can reduce this consumption – but how is the money best used for which type of building? Empa researchers have investigated this question. More.

Preheating of catalytic converters

The cold-start dilemma

With hybrid cars and plug-in hybrids, cold starts occur more frequently when the internal combustion engine stops and the electric motor pushes the car through town. How quickly can the catalytic converter be preheated so that it can still clean exhaust gases well? What would be the method of choice? A team of Empa researchers is investigating. More.

Self-learning heating control system

Smart heat

Can buildings learn to save all by themselves? Empa researchers think so. In their experiments, they fed a new self-learning heating control system with temperature data from the previous year and the current weather forecast. The “smart” control system was then able to assess the building’s behavior and act with good anticipation. The result: greater comfort, lower energy costs. More.