When electrons spin differently

Graphene nanoribbons: it's all about the edges

The perfect blueprint

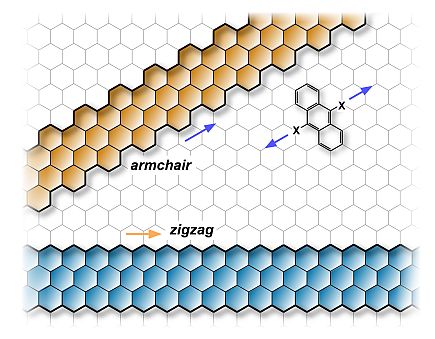

In the paper now published in Nature, the Empa team led by Roman Fasel reports, together with colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research in Mainz, headed by Klaus Müllen, and from the Technical University of Dresden led by Xinliang Feng, how it managed to synthesise GNR with perfectly zigzagged edges using suitable carbon precursor molecules and a perfected manufacturing process. The zigzags followed a very specific geometry along the longitudinal axis of the ribbons. This is an important step, because researchers can thus give graphene ribbons different properties via the geometry of the ribbons and especially via the structure of their edges.

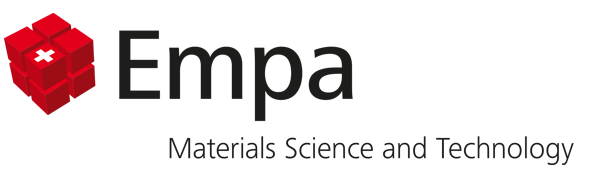

As with floor tiling, the right tiles - or precursor molecules - for the synthesis on the surface first had to be found for the specific pattern of the zigzag graphene ribbons. Unlike in organic chemistry, which takes the occurrence of by-products into account on the path to achieving a pure substance, everything had to be designed for the surface synthesis of the graphene ribbons so that only a single product was produced. The scientists repeatedly switched back and forth between computer simulations and experiments, in order to design the best possible synthesis. With molecules in a U-shape, which they allowed to grow together to form a snake-like shape, and additional methyl groups, which completed the zigzag edges, the researchers were able to finally create a "blueprint" for GNR with perfect zigzag edges. To check that the zigzag edges were exact down to the atom, the researchers investigated the atomic structure using an atomic force microscope (AFM). In addition, they were able to characterise the electronic states of the zigzag edges using scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (STS).

Using the internal spin of the electrons

And these display a very promising feature. Electrons can spin either to the left or to the right, which is referred to as the internal spin of electrons. The special feature of the zigzag GNR is that, along each edge, the electrons all spin in the same direction; an effect which is referred to as ferro-magnetic coupling. At the same time, the so-called antiferromagnetic coupling ensures that the electrons on the other edge all spin in the opposite direction. So the electrons on one side all have a "spin-up" state and on the other edge they all have a "spin-down" state.

Thus, two independent spin-channels with opposite "directions of travel" arise on the band edges, like a road with separated lanes. Via intentionally integrated structural defects on the edges or - more elegantly - via the provision of an electrical, magnetic or optical signal from the outside, spin barriers and spin filters can thus be designed that require only energy in order to be switched on and off - the precursor to a nanoscale and also extremely energy efficient transistor.

Possibilities such as this make GNR extremely interesting for spintronic devices; these use both the charge and the spin of the electrons. This combination is prompting scientists to forecast completely new components, e.g. addressable magnetic data storage devices which maintain the information that has been fed in even after the power has been turned off.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), the European Research Council (ERC) and the US Office of Naval Research (ONR).

On-surface synthesis of graphene nanoribbons with zigzag edge topology, P Ruffieux, S Wang, B Yang, C Sanchez, J Liu, T Dienel, L Talirz, P Shinde, CA Pignedoli, D Passerone, T Dumslaff, X Feng, K Müllen, R Fasel, Nature 531, pp. 489–492 (2016), doi: 10.1038/nature17151

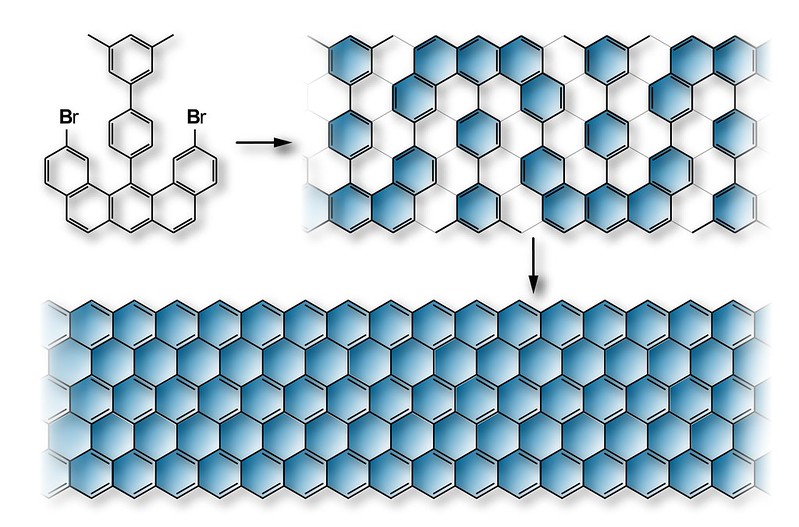

In collaboration with researchers at the University of Basel and other international colleagues, Empa scientists recently also studied the tribological properties of graphene nanoribbons. In an article in the journal Science, they reported on the interactions of graphene nanoribbons that, with the tip of an atomic force microscope, have been pulled in different directions over a gold surface. With these experiments and thanks to powerful computer simulations, the researchers were able to demonstrate that virtually friction-free, floating movements were possible. The reason for the smoothness (superlubricity) is that the two atomic lattices on the crystalline surfaces of gold and graphene are completely incongruent with each other; latching cannot thus take place anywhere on the atomic "rolling landscape".

Superlubricity of Graphene Nanoribbons on Gold Surfaces, S Kawai, A Benassi, E Gnecco, H Söde, R Pawlak, X Feng, K Müllen, D Passerone, CA Pignedoli, P Ruffieux, R Fasel, E Meyer, Science 351 (6276), pp. 957-961 (2016), doi: 10.1126/science.aad3569

Press release from the University of Basel

-

Share